Welcome to Listening In on Pandemic Life, a new ten-part monthly blog series curated by CASE in which artists, scholars and designers offer short reflections on their sonic experiences across the past 18 months of living under the shadow of COVID-19. The pandemic continues to affect everyday life on a global scale. Our sonic, visual, emotional, political, and economic realities shifted dramatically in the early months of the closures, and are evolving tangibly as the months pass. Many acoustic ecologists, artists and researchers have already noted the changing features of local soundscapes as a result of pandemic measures: less noise, new soundmarks, and most of all a newfound significance in the daily rhythms of life. Our aim in this series is to extend beyond the initial reactions to the sonic effects of reduced global movement and consider the lingering effects of our new reality as the world opens back up while the virus continues to propagate. This is our contribution to growing conversations about soundscape ecology and sonic cultures in (post)-pandemic times.

In this seventh entry to the series, digital artist Hali Santamas walks us through a disorienting transition from pandemic lockdown in the UK to a new life on Canada’s west coast. – Editors Milena Droumeva and Randolph Jordan

_____________________________________________________

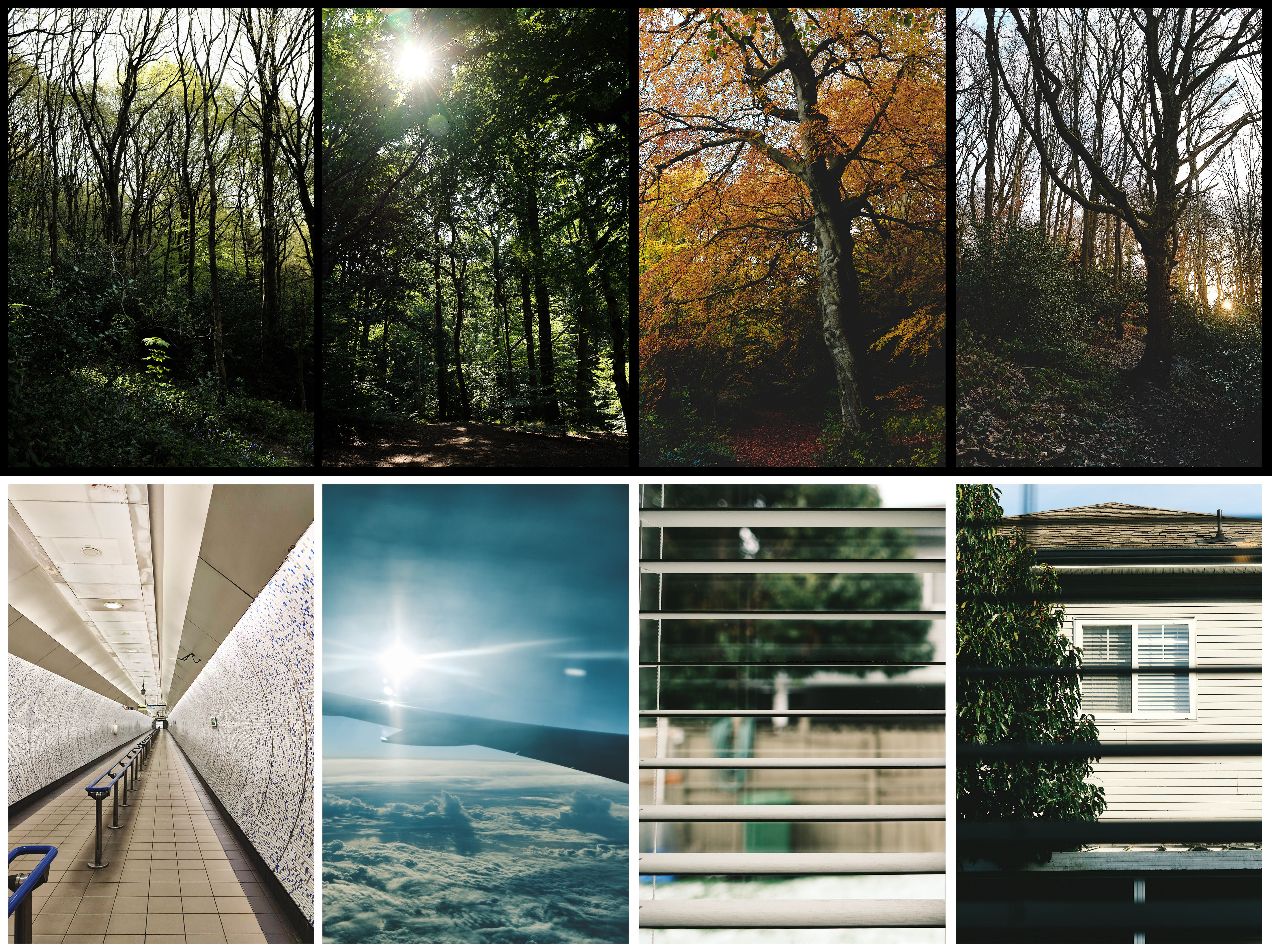

On the 23rd of March, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced the country was going into lockdown. Normal life ground to a halt and the world was suddenly, seemingly silent. We were only allowed to leave the house once a day for exercise so I started the habit of going on an early morning walk in Gledhow Valley Woods, a small wooded hillside with a stream and a lake, a few minutes from my house.

Though the COVID restrictions changed with the direction of the wind, I continued my morning walks, listening to the ebb and flow of the seasons. The cacophony of bird song in the spring, the gentle sway of leaves high in the trees in summer, the rustles and thuds of squirrels collecting food in autumn and the quiet, crisp crunching of frozen mud in winter. As the soundscape changed, I also changed. My thoughts, my routes through the forest and the frequency of the quiet click of the leaf shutter in my camera were all seasonal. As I carefully navigated my way down muddy paths my quiet presence in the soundscape blended in with the ever-shifting forest. I felt, possibly for the first time, truly rooted in the sounds of the place around me.

Moving to a new country is intensely sonically disorienting. The peace of my woodland walks was suddenly replaced with familiar yet alien sounds. When we arrived in Vancouver, the visceral rumble of our heavy cases felt endless as it reverberated eerily along long deserted underground corridors linking transit. The ever-present, unstable rumbling eventually yielded to the strangely familiar sounds of a surprisingly busy airport terminal with the uneasy background of frustrated would-be travellers’ desperate phone calls.

Beyond the officious hum of stamps and nervous conversation at the border, the soundscape of Canada was instantly soft. Snow muffled the previously omnipresent rumble of suitcases as we pulled them into our quarantine suite, the open door seemingly sucking away the sounds of the cases and the remnants of the roar of the airplane.

I thought the cars sounded louder than in England though perhaps their revving was just more significant. Every engine on the quiet, sterile street a potential delivery of food or sim cards or beer. When they left, everything went near-silent again.

The few birds we could hear sounded wrong. The tone was familiar but the tune wasn’t one I had heard before. The crows voices were too deep and there was something singing two pitches over and over like an elongated cuckoo clock. Then there were the snow geese. A cloud of endless honking drifting in from the distance, over the house and beyond the horizon. Strange disembodied and increasingly frantic honks punctuated the quiet of the suite on a regular basis. As the weeks passed it fed into an increasing quarantine-induced psychedelic feeling of being out of place.

As I write this, it’s three months since we got out of quarantine and the soundscape is becoming familiar again. I hope to one day feel rooted in the gentle pattering of the BC rainforest.

Author Bio:

Hali Santamas is an artist and academic from West Yorkshire currently based in Vancouver, Canada. He primarily works with digital sound and image, evoking memory and futurity through affective atmospheres. His art is characterised by its maximal layered, processed and abstracted use of recorded time. His most recent creative and theoretical works explore queer futurity, utopias, and the transcendent affect that arises from the temporal friction between still and moving sound and image.

Leave a Reply