Welcome to Listening In on Pandemic Life, a new ten-part monthly blog series curated by CASE in which artists, scholars and designers offer short reflections on their sonic experiences across the past 18 months of living under the shadow of COVID-19. The pandemic continues to affect everyday life on a global scale. Our sonic, visual, emotional, political, and economic realities shifted dramatically in the early months of the closures, and are evolving tangibly as the months pass. Many acoustic ecologists, artists and researchers have already noted the changing features of local soundscapes as a result of pandemic measures: less noise, new soundmarks, and most of all a newfound significance in the daily rhythms of life. Our aim in this series is to extend beyond the initial reactions to the sonic effects of reduced global movement and consider the lingering effects of our new reality as the world opens back up while the virus continues to propagate. This is our contribution to growing conversations about soundscape ecology and sonic cultures in (post)-pandemic times.

In this fifth entry to the series, presented as an audio essay with excerpted text, sound artist and critical race theory researcher Nimalan Yoganathan opens his ears to the “white aural gaze” pervasive in the streets of Montreal as we near the end of pandemic year two, considering what a return to “normalcy” means outside of the dominant framework as public health protocols enact differing privileges and restraints on differing sectors of society. – Editors Milena Droumeva and Randolph Jordan

______________________________________________________

As I take daily soundwalks through the affluent neighbourhood of Montreal West in Quebec, the mundane sounds of commercial activity and social gatherings may give the sense of a return to “normalcy” especially considering COVID-19 vaccination rates are on the rise. But I question how the notion of a “normal soundscape” is conceived through the white aural gaze.

In the early months of lockdowns during the Spring of 2020, acoustic ecologists and sound mappers were keen to listen to newly hushed cities and the re-emergence of natural sounds that had been previously masked by urban noise pollution. The supposedly silent soundscapes were of course interrupted when Black Lives Matter protests erupted across the United States and globally in June 2020 following the police killing of George Floyd. What was, just a few months prior, a soundscape of startling, if enjoyable, quiet had become a cacophony of raucous, but righteous, protest noise. Unfortunately, one year into this pandemic, we seem to be returning to the soundscapes of a neoliberal status quo.

While the quietude of lockdowns may have felt recuperative and soothing for many, the assumption that we all equally benefit from recuperative soundscapes during a pandemic is clearly a racially color-blind one. Racialized essential workers and unhoused people who were fined for alleged public health violations were not enjoying the same “hushed cities” that acoustic ecologists and sound artists were drawn to.

In an ideal urban context, recuperative soundscapes could be found in spaces where we are not expected to consume, work and be productive. Spaces where we can simply exist. In those spaces, the mere act of listening without “doing” can be radical and counter-hegemonic. Of course the neoliberal management and commodification of almost every public space in our cities makes finding recuperative sounds very difficult.

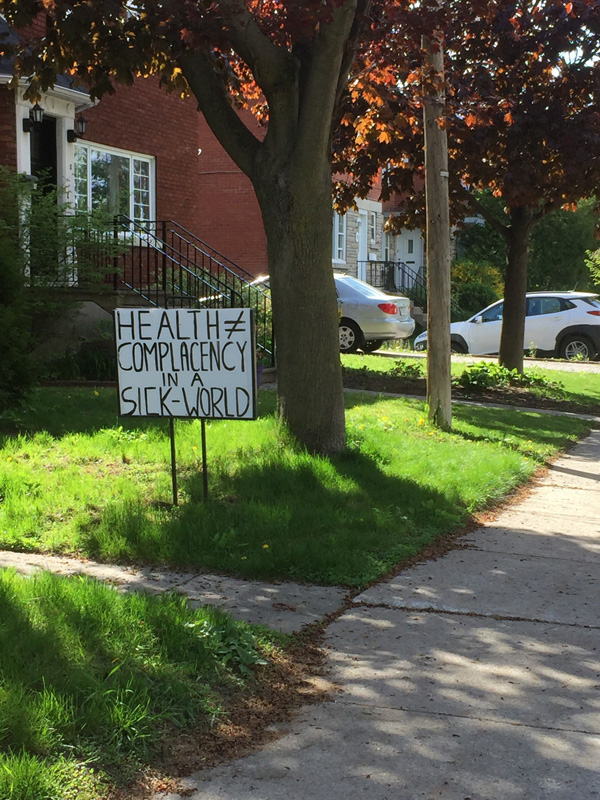

Soundwalking through predominantly white spaces like Montreal West as a racialized person often means my body is subject to surveillance by local public security agents and even by white dog walkers. I don’t have the acoustic privilege to stop and listen and to have my listening body take up space the same way that unmarked white bodies “extend into spaces that have already taken their shape” (Ahmed 2007). My restricted listening leads me to believe that the seemingly innocuous pandemic soundscapes that some perceive as “recuperative” and indicative of a “return to normal” are in fact masking something more harmful – that is, complacency.

The once hushed little town of Montreal West now has little pockets of noise re-emerging as summer months approach. I hear hockey watch parties with the sounds of commercials emanating from giant TV screens installed on people’s back patios. I hear the sounds of jubilant laughter and the clinking of wine glasses. It starts to sound like any other pre-pandemic summer night.

Acoustic ecologist Barry Truax (2019) defines a soundmark as any environmental sound of unique historical and cultural importance to a community. Perhaps for many white Montrealers, the familiar soundscape of communal hockey appreciation serves as a soundmark that brings communities together.

However, I hear these nightly noises as soundscapes of Western liberalism, individualism, and denial. I hear people performing what the white normative idea of a “return to normal” sounds like. Are these white listening ears (Stoever 2016) that are attuned to hockey soundscapes also hearing the testimonies of Canadian residential school survivors or news reports about the vaccine apartheid plaguing much of the global South?

I suggest we move beyond romanticizing what R. Murray Schafer terms “hi-fi” clear and quiet soundmarks and instead think through how urban noise can also contribute to our wellbeing. Loud music and noise when deployed as protest tactics by Idle No More or Black Lives Matter, for instance, can be recuperative and transformative. The noises of protest should be understood as indicative of marginalised communities coming together. Like soundmarks, these noisy sounds should also be preserved and multiplied. Protest soundscapes are one of many possible tools used to expose the façade of a neoliberal “normal” constructed through white listening positionalities. Listening to the past year of the pandemic suggests how there are multiple soundscapes operating simultaneously at the margins of society, and not just “quiet” and normative ones.

Works Cited:

Ahmed, S. (2007). A phenomenology of whiteness. Feminist Theory, 8(2), p.158.

Stoever, J. L. (2016). The sonic color line: Race and the cultural politics of listening. New York: NYU Press.

Truax, B. (2019). Acoustic ecology and the World Soundscape Project. In M. Droumeva & R. Jordan (Eds.), Sound, media, ecology. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

White, K. (2012). Considering sound: Reflecting on the language, meaning and entailments of noise. In M. Goddard, B. Halligan & P. Hegarty (Eds.), Reverberations: The philosophy, aesthetics and politics of noise. London: Continuum.

Author Bio:

Nimalan Yoganathan is a PhD student in Communication Studies at Concordia University. His work aims to bridge acoustic ecology with critical race studies. His main research interests include anti-racist protest tactics, decolonial and intersectional modes of listening, as well as quotidian forms of noise and silence as practices of resistance. He has presented his research at the International Conference on Arts and Humanities (Kuala Lampur, Malaysia), The Politics of Listening Conference (Sydney, Australia), and the Congress of the Humanities and Social Sciences (Edmonton, Alberta). Nimalan is also a sound artist who has conducted research-creation and field-recording projects in the Brazilian Amazon rainforest and the Inuit community of Inukjuak, Nunavik.

Leave a Reply