In this month’s post, CASE Chair Andrea Dancer takes us deep into the heart of her Kravin project to explore the art of soundscape composition as documentation of interspecies empathy at the edge of the human/animal divide. – RJ

By Andrea Dancer

Even Song

On the ridge over the fields up and behind “Behind the Village”

we breathe in the evening, the day melting, the sun slipping, listening

to chirping skies, clicking fields, rustling forests

that intone nocturne as they fold toward sleep.

A hare, large and listening, bounds through the tree line into grass,

where we become marked, overridden by the ultra-light,

a bluebottle engine drone overhead passing over and out

and away. The hare comes, close, mislead

as we are, human and animal, by the furore that mutes and

the confusion that follows. Ears erect and straining,

we hear only the screech, wail, and rumble of these, our places,

until our eyes and nose twitch, sending us into terror.

The sun’s now half buried by the horizons we create with our eyes,

while in their palace, ungodly cows moan out their lives tethered to meat –

like wind rustling wheat fields or the far off traffic rattling our bones –

their horrified hoofs undulate and rattle at our approach.

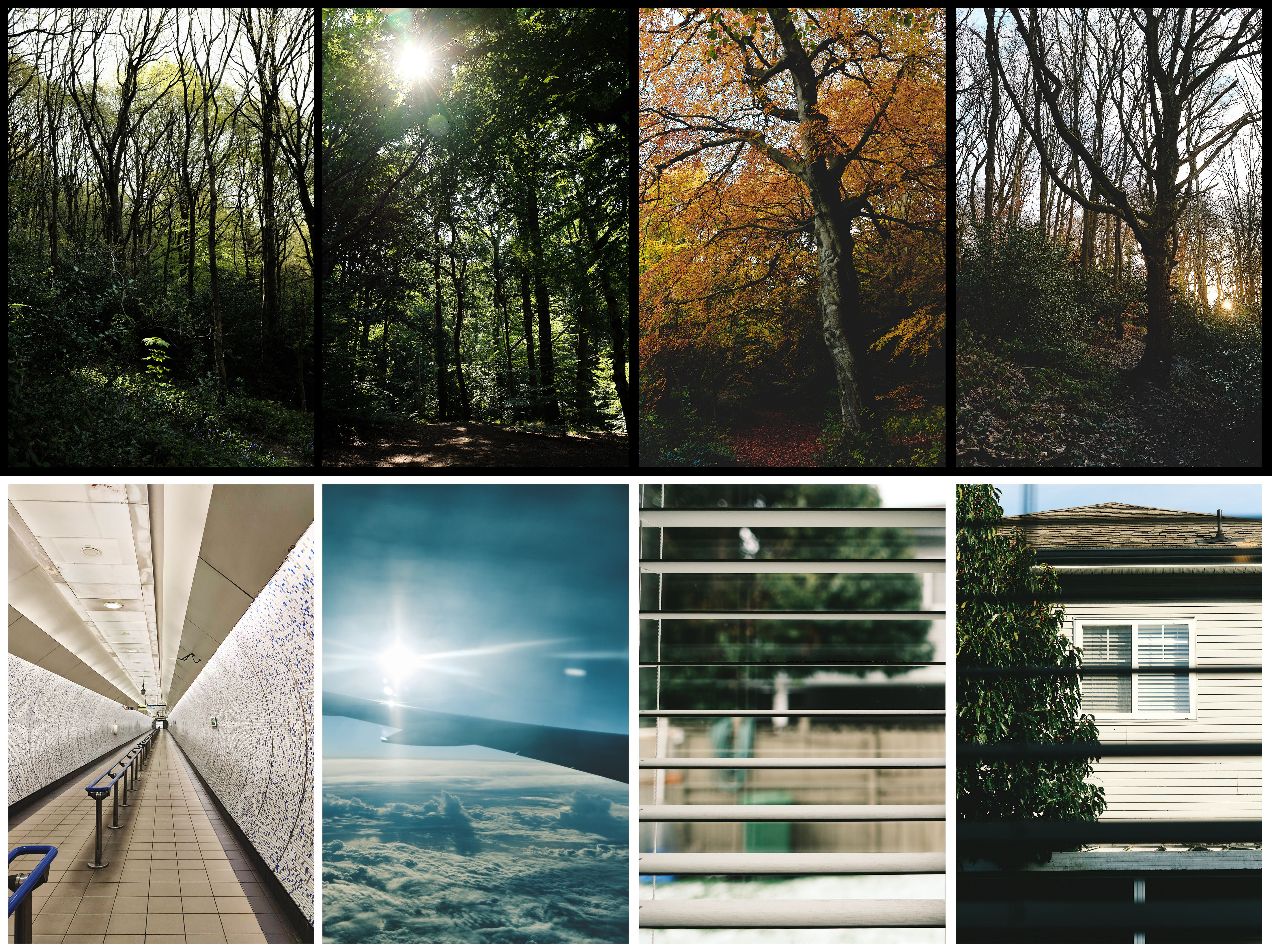

Inherent Elsewhere

Over the past eight years now, I’ve travelled from my home in Vancouver, Canada to spend summers in a farmhouse in a small village in the Czech countryside, a different home-place. The soundscape is well articulated there: the buzz and hum of insects, a yellow flying thing that (thankfully) doesn’t bite, and crickets and flies caught between the inner and outer windows underscore constant birdsong. Too many bird’s songs to try to name interlace the day, and at dawn in the spring they are like nothing else I’ve heard – so lush and varied.

A family of the birds, a type of swallow with a split black tail, lives in the barn in the part remaining from the original 17th century cottage where log beams are set in straw above long empty animal stalls (an early central heating system). Many generations of these swallows live there now. I enter the barn to be confronted head-on with anxious wing-flapping in my face. Intruder alert!

This year’s young chick is learning to fly when I arrive. I sit in the garden and watch early flying lessons. The adults can catch an insect for dinner mid-air. They fly fast and acrobatically. I’ve come to know swallow birdsong the best, complex and varied like several birdsongs in conversation at once – when it’s really one him with himself – and ending each time with a whirring tongue-clacking flourish. That’s when he actually opens his beak. I know it’s a male as he sits on the electricity wire over the apple tree under which I’m sitting, strikingly black with a burnt orange tail, while the female flits back and forth between there and the red tile roof of the cottage in attempts to distract me from her youngster. Not many creatures make it to maturity in this disciplined landscape, so no wonder at their concerted song and dance tactics.

Consistently, the utterances of chickens, roosters, cats, sheep and one sheep bell on the hillside crisscross the quiet and, as in all villages, dogs bark in the distance. Always somewhere a barking dog.

With 130 full-time residents here, most related to the original family (Bartos), everyone else exists somewhere along a continuum of foreigner starting with those who married in from surrounding villages to extreme cases like me, the only non-Czech — and Canadian at that. I speak hockey, know Indians, and make peace wherever I go (not). How I arrived here is another story.

During the summer, the activities of the villagers involve farming or building houses. On some weekdays, the dawn chorus of birds is broken by trucks with trailers lining up at the stone quarry. On most weekdays, tractors grumble past, the gravestone cutter next door makes hammering or stone cutting interjections, the sawmill sends a high pitched zing into the air, and in the evenings, lawnmowers and weed whackers keep grasses from the chaos that is the overgrown norm in our yard – as we are transients who arrive every one or two years now for a few weeks. By dusk, things quieten down.

On weekends, table saws whine, the traffic on the road increases with cottagers, a solo Harley motorcycle roars through overtaking groups of cyclists, there is usually a wedding at the Cultural House in the centre of the village, sometimes there is music at the pub along the road or at the summer camp on the edge of the forest or sometimes just the voices of children playing in the sports field drift my way. I sit on the rise of the hill behind the cottage and watch the sun set in one direction and the moon float over the forests and fields in the other direction. A black cat stealths through the field of wild flowers at my feet as I listen to the day ending, as the village sinks into dark and a dankness creeps into the valley.

Between this village and the next, in hillside folds, a large red roof crushes down on a warehouse-like building. A few smaller buildings cluster round the enormous one and the whole compound recesses in the crux of three hillsides with fields in all directions and a ridge of forest at the top of each hill. From between these slopes, muted groaning and shuffles haunt the breezes that gust past my ear, catch, then pass. Snatches of covert things and conversations.

One morning, I trudge towards that place where I’ve been told unwanted kittens are deposited to meet nature’s fate. Nature, in such countryside, lurks far far inside a long-historied will to subvert any wilds, although wilderness (especially Canadian wilderness) catches imaginations here. Wilderness left Europe a long time ago, but there remain degrees of adherence to concepts of nature.

A woman told me that, before the end of the 1960s in a more liberal era of Communism, the village cow herd pastured in the forest behind her house. She thinks they were cows for milk, not meat. She still longs to hear their bells over the countryside as it was somehow comforting to her – it kept her company in the solitude of being the last house before the forest and in her life with an often absent husband. She said she marked the end of daytime and the approach of evening when she heard the cowbells approaching at the back of her house. Their proximity and light-hearted clanking signalled a kind of all’s well that she’s missed ever since. With the 1970s Communist crackdown in Czechoslovakia, farms were treated as industrial collectives and each village was its worker base. In fact, the old cow barn is one of the buildings in the barn complex, now derelict but small and quaint. Someone has put up a plaque declaring that the last animals were housed there in 1967, ironically the last year of moderate Communism just before the Prague Spring of 1968. The era of normalization marks the brutal Communist crackdown on Czech citizenry and plunder of Czech resources bound for Mother Russia and the current industrialized cattle facility was built and put into action in the village. When Communism ended in 1989, these collectives reverted back to the villages, which is how it is today – but the pastured cow herd was never reinstated.

Sometimes, when I’m walking in the interstices between field and forest, I stretch my ear to imagine the cow bells, random and unseen, conjuring a call home to a warm mug of milk. This stands in contrast to the silence of the cattle facility.

Most villages have a kravín, a large scale cow barn. I’m a city girl, so don’t have the pragmatism of country folk. I’ve lived in proximity with horses, cats, dogs, chickens, ducklings, rabbits, budgies, and an iguana, as companions – but never as food. I luxuriate in the premise that all life carries consciousness and a right to equitable treatment. I adhere to the premise that animals are fed before I sit to eat. For animals, eating is a social activity, and why should they do without while I satisfy my needs? I sit firmly in the camp of sensitive animalist.

I take my bike and ride through the village up the hill road out of one village towards the next and on to the cow barn. I’ve never been there before but I’m curious about the muted quality it exudes. Everything seems to bypass it. There are never cars or trucks in its driveway, I’ve never seen anyone there. It resides in an elsewhere, on a road from somewhere to somewhere – and in my life, I feel a kinship with that somewhere-in-between.

I take my camera and audio recording equipment. I take the road and then approach through a field rather than take the stark white oversized driveway up to the barn compound in order to approach the warehouse’s colossal double doors, which are locked shut.

I hear muffled shuffling and puffing, like a dormitory full of bodies turning in restless sleep.

Kravín: The Cow Palace

This project begins as a documentation of a part of the village, the cow barn, remnant of a communist way of life and cooperative farming. Initially, my companion and I refer to it satirically as the “cow palace,” the village villa for cows. In this way, it starts quite innocently with a curiosity about this eerily silent place where hundreds of heads of cattle are kept – a big red and silver roofed mystery. Perhaps there is a cat lingering who will catch mice for the farmhouse, I think to myself. In my time recording there, I don’t see a trace of a cat.

The cattle barn, once inside through a feed opening, knocks me back, appals me, and slices through me with the indifference of the butcher knife. Miles of bodies pressed against one another, unbelievable stench, blasts of hot breath, a sea of single black eyes with singular expressions, mires of shit on hoofs and knees and up to foreheads. Crowding and humping. Lowing and low moaning. All in quiet.

From what I read and understand, in fascist and repressive regimes, humans are treated like cattle. Human life improves under capitalism and free markets, but there is little trickle down to animal welfare here. Some treatment is better than others, but whether pet or domestic animal, both are intended to serve humankind’s end. Dogs are guard dogs. Cats are semi-feral, not spayed and meant to catch barn vermin. Many kittens are left “to nature’s way” as one resident put it, although many are drowned or crushed by the farmer and few survive. An adult cat’s life lasts only a few years. At the end of the street where I stay, two different sheep each year live for the summer months without food or water and under horrendously hot coats without any discernable grooming or care. They nibble at sparse tufts of grass that diminish if it doesn’t rain. Today topped 40 degrees. I think about the sheep as I drink water to stave off a headache and exhaustion. I dare not venture to the end of the street to see how they’re doing. Last week, I put a bucket of water in their yard, but someone removed it. Better not to meddle.

I recognize that in this I am foreign, as I cannot tolerate any type of creature or human suffering. Of course, this reveals things about my personal background. As someone familiar with the outcomes of trauma, I also know that its avoidance isn’t always possible. I remember watching a student video of a Romanian villager taking his most beloved pig – all the while singing loving songs and calling her “Darling” and petting her quite sincerely, teary eyed – up to the place where he would, in one gesture, cut her throat at slaughter. There is no judgment intended, just recognition that my sensibilities are bound up with something quite different. I still hypocritically eat meat from animals whose lives and deaths entail unspeakable suffering and don’t generally think about it when it comes neatly packaged. On some level, making the audio recordings of the cows whose lives are spent locked up in the cattle barn becomes a means to break a profound silence around the suffering of animals, and perhaps my own, and a way of facing this acknowledged obliviousness.

I can only begin to acknowledge the suffering inflicted with impunity on children and people in situations of abuse on a daily basis in my own city and in the communities I encounter, let alone worldwide, if I acknowledge the suffering inflicted in similar ways on animals.

I only go to the cattle barn once, make these recording over several hours, and know I will never return.

I never return in person but the recordings mark countless returns.

Listening Salon: Cowcaphony

2’54” – Stereo – 96000 hz – 32 bit float – wav files on M-audio Microtrack II – Stereo T Microphone

[For an optimal listening experience, listen in a quiet room with high quality headphones or speakers. This and related tracks archived here.]

* * *

I am the bird sitting in the tree, the one who sings and observes and is free to flit away at will.

I am the woman standing at the door, the one with her hand open and stretched forward through the bars of the gate.

I am the master, the one recording, the one who touts self-awareness, that supremely human privilege, and who wants to walk away but can’t.

I am the one at the trough, microphone in hand, the one who cries for a hand in the night, assurance that I will not be led to the slaughter like so many all around and before and to come.

I live for that assurance. I mount that assurance.

Then, it mounts me. I am the one who cannot get away.

* * *

Compound Explications

The kravín project is relatively compact with myself as participant and producer. It is an early foray into soundscape composition and therefore a reasonable starting point for experimentation on how to unpack and explicate soundscape composition. Although the process in later works evolves to align closely with soundwalking, this project uses audio recording as documentation as well as story, as an educative and creative tool with an activist edge in the process of creating a soundscape composition.

The intent was to document a soundwalk through the cattle barn compound as it was occurring. I knew it would have specific expressive sounds: metal against metal (doors, gates, fences), the sounds of cows (utterances, bodies in a confined place, breath) set against the open sound-space of the village. Also, I wanted to express the quality of the silence I associated with the place. It was originally intended to be my contribution to the World Listening Project (World Listening Project, 2013), an annual online festival and sound map to mark R. Murray Schafer’s birthday, so I know the date it took place – July 18, 2010. It never did meet that aim.

What begins as a soundwalk quickly becomes a focused recording session as I am transfixed by the encounter. It becomes something I can’t walk through, but have to stand inside of and listen. In this way, the work differs from later compositional strategies where I create a public soundwalk, enact it without any documentation, and then record it after the fact using various recording methods and microphones. In that approach, emphasis is on movement through acoustic space, walking and listening to a sequence of sound events along a route designed to enhance awareness of the soundscape. The kravín recordings happen all at once while I experience it. The experience overwhelms.

I use the four-channel microphone array that came with the audio recorder, a T bar with one stereo pair at each end. At the kravín, I position the array close to the sounds I want to record, sometimes with the subject between the T to emulate surround and other times with one of the mic pairs directionally centered on the subject and the other on the background sounds. But when faced with the cattle, literally, I am caught between the experience and the one who records the experience. This tension is heightened by the intensity of the encounter and, as a result, the recording is rather catch as catch can. The interesting compositional aspect is just this immediacy, which is also expressed in the urgency with which the cows respond to me, increasing their shuffling and utterances as I linger in the space.

In later soundscape composition field recordings, technique and preparation become refined and, in this sense, the experience mediates the real time moment of recording in anticipation of the end product. I had no end project in mind when I recorded at the kravín. As John Cage points out (1961), this is the optimal compositional sound-to-listener situation: where the artist is fearless in attending to the sound as sound with the full force of impact in an embodied listening experience pushing it forward. This force resonates forward over time in the recordings. For subsequent listeners, the meanings change but the initial emotional force carries that meaning as potentially profound; such was the case for me in what I initially experienced. My intention for that day was thwarted by a much different and challenging acoustically-based experience.

This is communicated in both the raw recordings of what was happening as I approached these creatures who were obviously reacting to my presence and, if I have accomplished my aim, in the final composition as an expression of what I experienced.

Why did the cows react with such utterances? Perhaps I represented an unanticipated feeding in a regime that positions feeding time as the only contact the cows have with the outside world. Perhaps they simply craved stimulation other than each other. Perhaps, as I felt, the cows experienced a receptive and sympathetic presence – as I listened, made eye contact, and recorded attentively and with stillness to what they were articulating. I will never know for certain, and while most were silent and wary, a few pushed their noses through the bars toward my hand, breathed short hot breaths onto it, and then bellowed and moaned for some time afterward with me still in their gaze. In this exchange, I felt a tragic song, an attempt at communication, a reaching out for solace in an impossible situation.

In such an intense soundscape, what I want the world to be is blown apart and I face an unanticipated sense of something essential in the experience.

Alien Reception

In retrospection, I realize the profound sense of alienation at the heart of human angst was driving me, as part of a human and creature swarm grappling with the singular aspects of mortality, to explore how sound as a medium, as non-verbal and vibrational commune-ication, potentiates the experience of an alienated self/other.

Three months had passed while the cattle recordings sat, unattended. Revisiting them, listening again from a distance, I was sucked back into their sensual force, a deep empathy and desire to receive their articulations, to be open to them, whatever they meant. I grasped that the vocalizations of the incarcerated cattle, the intimacy of the encounter, the tenor of the sounds and their sensuality, and the exchange – the desire for connection and escape from insufferable circumstance and looming death – all spoke erotically. And so the idea of an “erotic of sound” emerged.

With this project, the experience, documentation, recordings and then the final composition constitute a study in how one early acoustic composition came into being in the trajectory of my work as a soundscape composer. Its potency lies in the force of the experience of those powerful articulations, sounds that bridge between human language – and its attendant meaning-making – and the voice of the other, utterance as language where meaning lies in the emotive force of the sounds themselves. It represents an important point of departure in coming to compose with sound as sound and inviting dislocation, conceptually and materially. In order to attend to sound as other, as self in other, the listener is called to loosen and unhinge their urge to codify meaning in the habitual way of humans – through human-centric language.

This is the call toward an ontology of listening through excess – can a listener listen to the alien being of the other and, in doing so, realize and recess the associations and codifications of habituated listening that stories human ways of knowing and being?

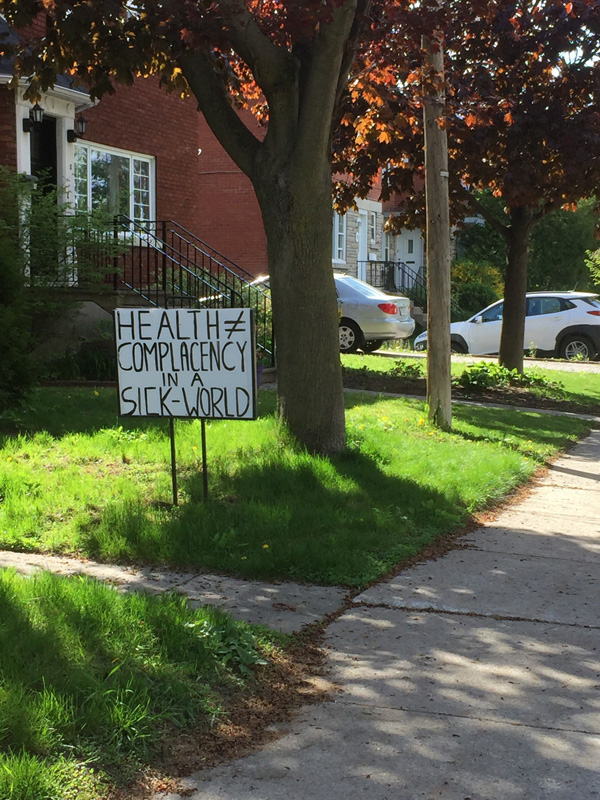

Can humanity not, in this way, begin to shift environmental complacency – evident in human inhospitality toward one another and all planetary existence – through such a turn around utterance as sound as expressive of self / other?

Does this not shift the spoken word as an interpreting mechanism toward sound for sound’s sake, as utterance? Does this evocation of finding the alien other in the location of a dislocated self not strike at the heart of a poetics of a listener-to-soundscape trope (Breitsameter, 2013, 17-36; Dancer, 2014, p. 61-63)?

These questions emerge out of this early happenstance of audio recording meant as documentation of an unknown part of somewhere I was sojourning, somewhere where I was living and seeking belonging to place and land knowing I would never belong. In a village in the Czech countryside, even a bride from a neighbouring village is a foreigner. Without even language, I was profoundly displaced. And this was the opening. The foray into a silent foreboding place led to an experience of myself as alienated finding connection through the alien communications of a radical other – incarcerated cattle.

The audio recordings of that encounter become the composition, which then finds new meaning as part of an online audio exhibition, Erotics of Sound (Dancer, 2010a) and then part of educational program (Fulková et al, 2010, 2011, 2012; Flynn, 2010) for a major arts exhibition (Studio Mandragore, 2010) dealing with decadence as an the idea and literary / artistic movement. Eventually, the composition is shown in a darkened cinema where the audience anticipates light on a screen, but instead is compelled to listen in an unanticipated moment in between the decadent films of an adjunct film festival.

This trajectory shows the mutability of sound, acoustic-based meaning-making mechanisms, and an artistic trajectory in excess of anticipated aims. Working with sound invites flux and fluidity continually in excess of the origins of its making as it travels toward unknown encounters. Sound, in this sense, aligns with an erotic exceeding sensate singularity – overriding the propensity of visual-based ways of knowing and being. In this way, acoustic ways of knowing and being have the potential to be an invitation, rather than a confrontation, to that which is seen as alien.

Bibliography

Breitsameter, S. (2012). On the history and perspective in R. Murray Schafer’s Tuning of the World. In A festschrift for R. Murray Schafer on the occasion of his 80th birthday. Hochsule Darmstadt: Service Printmedien, 17-36.

Cage, J. (1961). Silence: Lectures and writing. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Dancer, A. (2014). Profound listening: Poetics, living inquiry, arts-based practice and being-presence in soundwalk-soundscape composition (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved November 27, 2014 from cIRcle, University of British Columbia Dissertations Publishing, http://hdl.handle.net/2429/50833

Dancer, A. (2010a). (Curator) (2012, March 11) The erotics of sound. (online sound art exhibition). Retrieved July 5, 2013, from http://eroticsofsound.wordpress.com/

Dancer, A. (2010b). (Audio Artist, Producer) (2010, October 20). The love of meat. (audio art piece). Retrieved July 5, 2013, from http://eroticsofsound.wordpress.com/andrea-dancer

Derrida, J. (1994). Schibboleth for Paul Celan. In A. Fioretos (Ed.), Word traces: Readings of Paul Celan (J. Wilner Trans.). (pp. 3). London, UK: John Hopkins University.

Derrida, J. (1985). The ear of the other. NY: Schocken Books.

Derrida, J. (2008). The animal that therefore I am. New York: Fordham University Press.

Fulková, M., Dancer, A., & Hník, O. (2010-11). V černém oblaku. Edukativní program k výstavě Decadence Now!. [The Black Cloud Ritual: The educational program for the Decadence Now! exhibition]. Praha: Galerie Rudolfinum.

Fulková, M., Dancer, A., & Sehnalíková, V. (2010-11). Naruby. Edukativní program k výstavě Decadence Now!. [Insideout. The educational program for the Decadence Now! exhibition]. Praha: Uměleckoprůmyslové museum v Praze.

Fulková, M., Hajdušková, L., & Sehnalíková, V. (2012). Muzejní a galerijní edukace. vlastní cestou k umění. [Museum and gallery education: Your own way into art]. Praha: Univerzita Karlova v Praze, Pedagogická fakulta; Uměleckoprůmyslové museum v Praze.

Flynn, M. (Director). (2010). Black cloud ritual [Video/DVD]. Prague, Czech Republic. (Available from Charles University in Prague, Department of Art Education, Faculty of Pedagogy, Magdalény Rettigové 4, 116 39, Praha 1.

Studio Mandragore (Director). (2010). Decadence now! Visions of excess [Video/DVD]. Prague, Czech Republic: Galerie Rudolfinum. Retrieved September 11, 2013, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J5mDJxJJEcI

World Listening Project. (2013). The world listening project. Retrieved December 10, 2013, from http://www.worldlisteningproject.org/

Bio

Andrea Dancer is a writer, soundscape composer, acoustic arts-based research practitioner and educator, and Chair of the Canadian Association for Sound Ecology.

Leave a Reply